I first published an earlier version of this Article on Entrepreneur Magazine.

Read why you can’t apply the rules of legacy markets to new business models. And read why the term “disruption” is great for scaring people into buying books and courses, but fails to facilitate new perspectives.

In 1995, Clayton Christensen developed the “disruption theory.” Since then, the term has not only caught heat as a buzzword, but the theory’s core concepts have also been extended and misinterpreted.

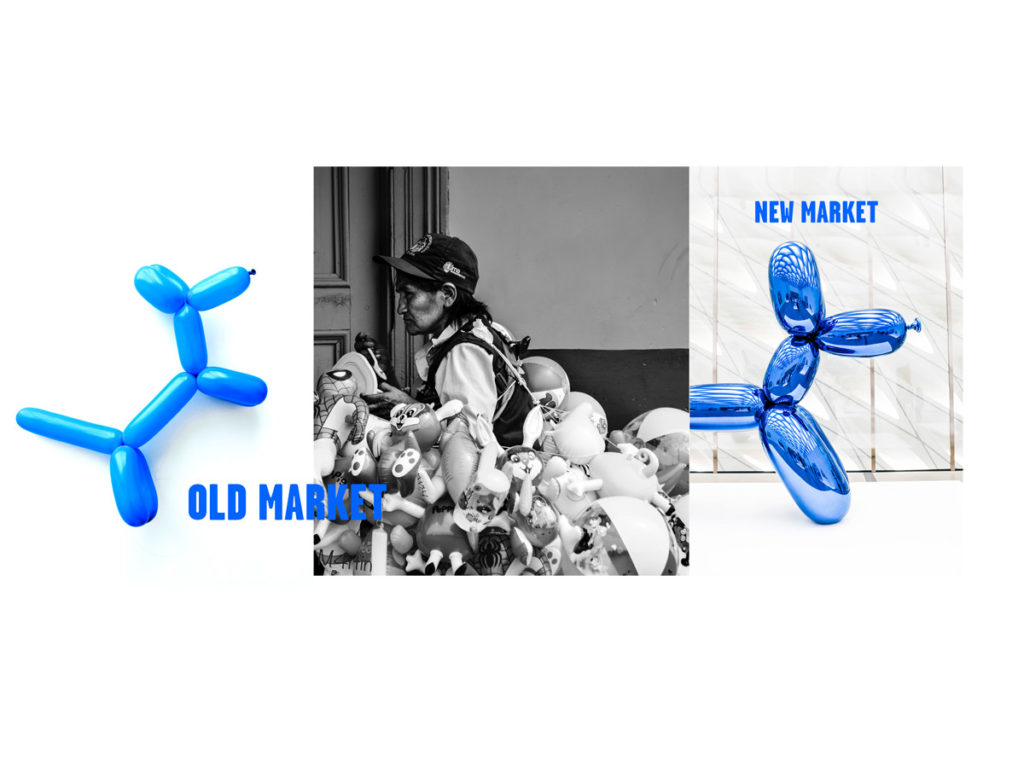

However, the correct definition of disruption is only a subplot. The problem with thinking in terms of disruption, whether correctly applied or not, is that it locks businesses into their legacy perspective. By definition, a disruption is the interruption of something existing.

Yet, when an industry is transformed, more often than not a completely new market is created. This new market has little in common with the legacy market. This is why we should view the transformed market through a new lens.

In reality however, we unfortunately see businesses trying to apply old tools to new rules. In particular folks who talk about “disruption” tend to focus on the old market and the old rules.

An example of transformation

For the greater part of the last century, the automobile industry was a metaphor for stability. German, American and Japanese powerhouses steadily churned out huge volumes of cars offering top performance and quality, while generating attractive profits for investors and stakeholders. For decades, there was little substantial change in vehicle design and neither was there any movement on the leader board. Some had better years than others, but the key players remained the same.

Now the space has changed. Traditional car manufacturers are in the process of adoption. Ford brought on CEO Jim Hackett, who previously ran design-driven office furniture company Steelcase and who has outlined a forward thinking six-point plan for Ford’s future. Not quite the vita that automotives would have envisioned a few years ago.

In this current auto industry power struggle, Tesla is viewed as the disrupting force, the David that fights against the Goliaths. Not too long ago, former VW CEO Matthias Müller had bashed Tesla for being the champion of announcements not products, ridiculing the company for burning money and having tiny unit sales volumes compared to traditional manufacturers.

A new market

But is Tesla really the David? Can its unit sales volumes provide us with an indication of who will win this battle?

The problem is that this not about changes within the traditional market. This is a new market. Comparing the volume of Volkswagen and Tesla in the old market is like comparing apples and pears.

The automotive market of the last century has been commoditized and will decline. This is not where the competition will take place in the future. The future of transport is an emerging market, which is still tiny today, but which is set to grow rapidly. While Müller may have been quick to ridicule Tesla for its output and burn rate, in new markets innovation takes time and output is low in the early days. This is the nature of the Technology Adoption Lifecycle.

If we consider the manufacturer of “future” cars, Tesla holds the largest volume. Tesla has not been catching up. Volkswagen is the contender in this new market.

New markets, new rules

In new markets, new rules apply. For example the processes of developing and building cars is changing. The machinery required to build cars is changing dramatically, because electric cars have less mechanical complexity. While mechanical complexity is being reduced, automated driving is increasing the software complexity.

At the same time the integration of the connected car within the internet of things will require the integration of a new mobility infrastructure, the ability to analyze the user’s context information and a UX design that provides users with the best options based on that context information.

Tomorrow’s car is not a mechanical car, but a software device and an information unit. The most important part of a new car will not be its engine, or its horsepower, but its analytical and design capabilities.

This will also change the criteria by which consumers will choose between car models. Factors such as auxiliary connectivity services will play as much as a role as the user interface of the “software product.”

Aside from new purchase criteria, the future will also bring new ownership models. With the rise of the sharing economy, cars will have to find their place in the bustling, congested smart cities of the future.

Therefore, when view the automotive market as a new market early in its life cycle, it is easier to understand why Tesla has never been too much concerned about his lower production volumes. We also see why Ford has ramped up its design capabilities at the board level.

New rules, new approaches

The rules of this new market, not of the old market, determine how a company has to approach its business. They determine what type of resources the company has to build up and how it addresses and reaches customers.

If an automobile manufacturer tried to enter the aircraft business, it wouldn’t even think about hiring automotive executives to manage the transition. It would look for someone who is well versed in the industry it was moving into, not out of. Yet, as Mueller’s statement has illustrated, leading car manufacturers’ executives have long been thinking of the current mobility market as the same market they cut their teeth in.

The current shift of automotive is often compared to the evolution from horse carriage to car. Here is the problem with this comparison:

The horse carriage served the same purpose as the car: getting from A to B with a device as quickly and safely as possible. The device that gets us from A to B, the traditional car, is a commoditized market.

The car of the future has additional use cases: customers’ purchase criteria will not solely be driven by which car is more reliable or faster. More important questions will be, for example, which vehicle is smarter and has the highest processing power.

Lessons to be learned

The automotive industry is just one example. The same lessons apply to any other industry that is being “disrupted” by emerging technology.

We would not measure an online media business by the same standards as a traditional print newspaper business.

Neither would we judge iTunes and Spotify by the same standards as the traditional music industry.

Airbnb does not play by the same rules as hotel businesses.

For any industry that is being transformed, we need to shift our perspective. We have to view the transformed environment as a new market.

Step one: understand the differences between the new businesses and the legacy businesses.

Refresh your perspective. Understanding how the businesses differ helps us understand the distinctions between the new and the old market. Here is a simple trick: have a look at the recruiting websites of legacy business vs new businesses. The areas they hire in will provide you with valuable insights of what type of resources they are building up.

Step two: assess the requirements of this new market.

Before allocating resources to the new challenges, figure out what customers want and what new rules exist in this new market environment. What are the purchase criteria of customers in this new market and how do they differ from the old market? What capabilities will drive the success of businesses in this new environment? Is it mechanical engineering, software or design? Is it hotel locations and service or the reviews and trust of Airbnb’s website?

Step three: question whether any legacy operation can still compete in this new market.

Which parts of any legacy business are still suited for this new market? Which parts of traditional OEM’s are necessary to compete in the new mobility markets? The answer to this question could mean scrapping legacy production methods or processes, or simply bringing on a new leadership with experience in the new industry, as Ford did.

Simply put, if our legacy business is building furniture and we were to enter a media business, we would immediately plan to start from scratch. Yet, when companies who feel being “disrupted” enter transformed markets, they still tend to think in terms of legacy business models.

Like any architect who designs a new building for a new environment, we first need to go back to the drawing board. We need to question existing assumptions and take steps to adapt to a new environment like Ford did, rather than resting on our laurels, and risk becoming irrelevant.